Elsner’s work focuses on combating vision loss. By developing techniques in retinal imaging and visual function, she and her colleagues have discovered several unexpected properties of normal and diseased tissues. Using novel light sources, Elsner has imaged structures that had never been seen in living tissues; this work is published in over 100 papers and was honored in 2018 with the Edwin H. Land Medal from Optica and the Society for Imaging Science and Technology. She is a fellow of the Optica, the Association for Research in Vision and Ophthalmology, and the American Academy of Optometry. She has extensive service as an editorial board member, a guest editor, a symposium organizer, and a reviewer for peer-reviewed articles and grant proposals. Elsner received the IU Bicentennial Medal in March 2020 in recognition of her distinguished contributions to IU.

Most recently, the American Academy of Optometry named Elsner the 2022 Charles F. Prentice Medal Award recipient. The award is widely considered the academy's most prestigious for achievement in research. Elsner will be recognized at a special ceremony during the academy's 2022 annual meeting Oct. 25–29 in San Diego.

Q: Tell us about your family history with IU. Who was the first in your family to graduate from here, and what did they study?

A: The first person in my family to study at IU was Hiram E. McDonald, my great-grandfather. He was a mathematician and was encouraged to continue his work in the math department but left to start a business and a family. Family lore is that he continued calculus competitions on his lawn on Sundays. The strong family tradition led me to choose IU.

Q: How did you settle on vision science as your research and career focus? What is the highlight of your research and work at IU?

A: I settled on vision research because I love color vision and art. Here are three highlights:

- While at IU, I obtained funding to work with collaborators to screen thousands of underserved patients for diabetic retinopathy, while collecting data that support both quantitative imaging and health care inequity research.

- I perform laboratory research in diabetic patients with my husband, [IU School of Optometry Professor and Associate Dean for Graduate Programs] Stephen Burns, and other collaborators here at IU, finding tangles and loops in smallest blood vessels in the retina of diabetic patients before these reach the clinical classification as abnormal. Another startling finding is the evidence of cone photoreceptors living in patients’ eyes but surrounded by dead support cells due to age-related macular degeneration. These cones are able to do their job, i.e. guide light, which flies in the face of conventional wisdom.

- Recently, we found that some parts of the retina have more cones, not fewer, most likely because surviving cones move over to be nearer to their support cells. Our work provides hope of battling eye disease at earlier stages and restoring some vision that was once thought to be completely lost.

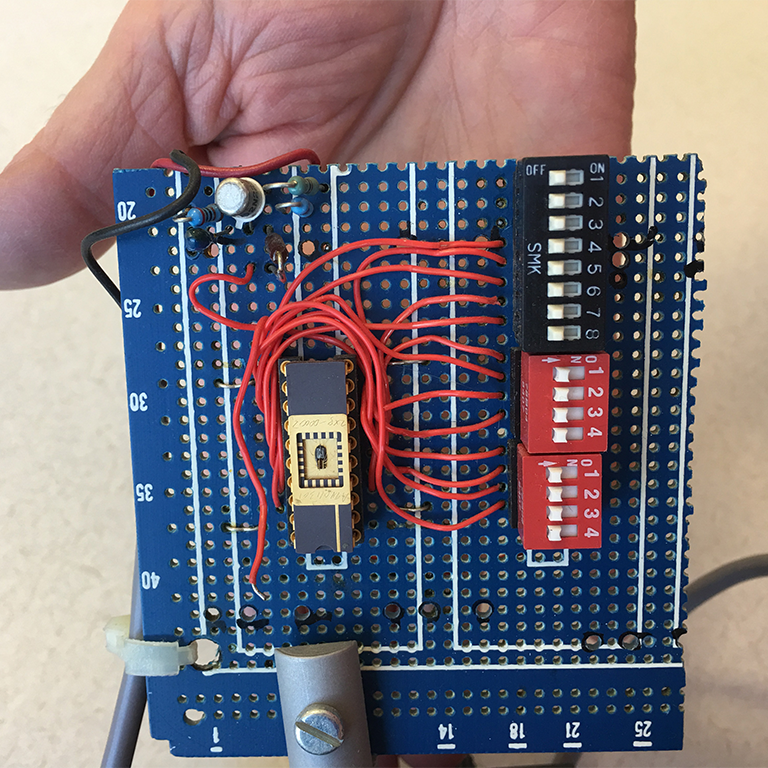

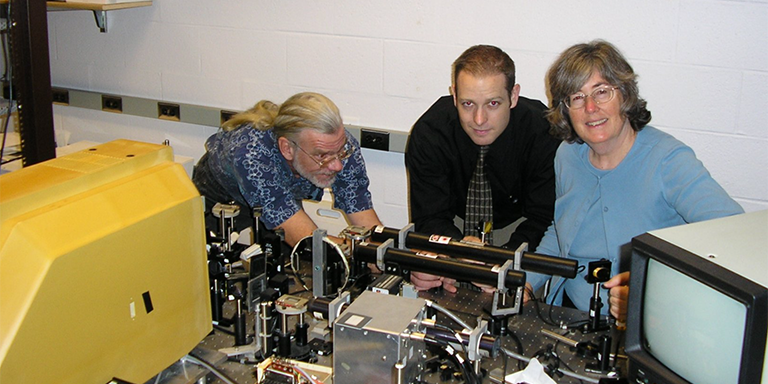

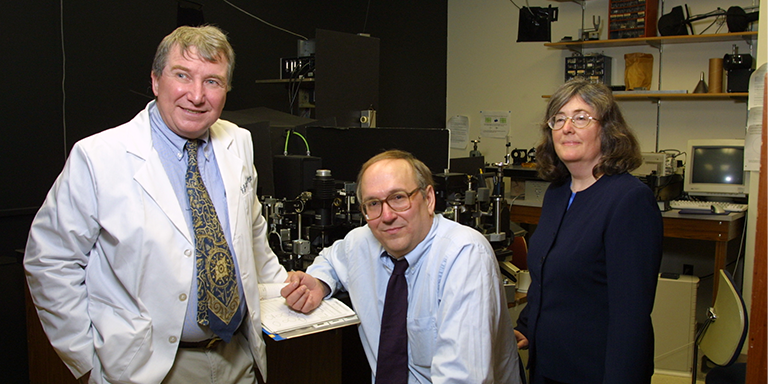

Left: An array of tiny lasers, called vertical cavity surface emitting lasers, provide images of the retina with miniaturized parts. Ann Elsner was the first person to make biological images with this new kind of laser. Top: Ann with her first grad student at IU, Dean VanNasdale, along with Bryan Haggerty, a software engineer in her lab. Shown is the scanning laser ophthalmoscope that Ann built, which allowed her to use near infrared light and other laser sources to produce high quality images of the living human retina. The optical breadboard is covered with a variety of lasers of different wavelengths. Bottom: John Weiter and Stephen Burns with Ann while collaborating in Boston on research to measure damage in patients with retinal disease.

Q: What are you working on currently that you’d like to share?

A: I just was awarded a patent to improve the accuracy of visual function measurements in older eyes. The problem right now is that many promising new drugs to combat retinal disease fail to be approved due to inconclusive visual function results. Also, we continue to analyze years of our diabetic patient data to understand when and how unwanted new blood vessels form in the retina, and what damage occurs to neurons.

Q: What’s your favorite part of campus?

A: I love much of campus, particularly the IMU and the IU Auditorium. Campus is my favorite part of Bloomington. The IMU has beautiful landscaping, interesting architecture, excellent cookies, and a plaque to outstanding seniors that includes my daughter, Rebecca J. Burns. The IU Auditorium has decades of happy memories for me, including 1968-1972 shows when Herman B. Wells could be seen and events from 2005 on, with family and friends.

Q: What differences do you see between the field of vision science when you were earning your doctorate and today? What kind of advice do you offer your students?

A: As a graduate student, I chose from a wide variety of graduate-level courses. These were at a high level, focused, and featured intensive interaction between a small group of students and one or more faculty members. Today, graduate-level teaching is little emphasized, and not even available in some programs. I advise students to learn their field broadly, not just their thesis project, and avoid being a one-trick pony.