Jeff Holdeman

Director of Undergraduate Studies

Senior Lecturer

Slavic and East European Languages and Cultures

Jeff Holdeman earned his Ph.D. in Slavic Linguistics from Ohio State in August of 2002 and began his work at IU three days later.

Jeff Holdeman

Director of Undergraduate Studies

Senior Lecturer

Slavic and East European Languages and Cultures

Jeff Holdeman earned his Ph.D. in Slavic Linguistics from Ohio State in August of 2002 and began his work at IU three days later.

His main research interests lie in the history, language, names, and identities of the Russian Old Believers in the United States and in their previous homelands in diaspora in Poland, Lithuania, Latvia, Estonia, Belarus, and Ukraine. He has been conducting annual ethnographic fieldwork in Poland and Lithuania since 1999. His current projects include an English-language translation of the most significant book on the history of Old Believers in Poland.

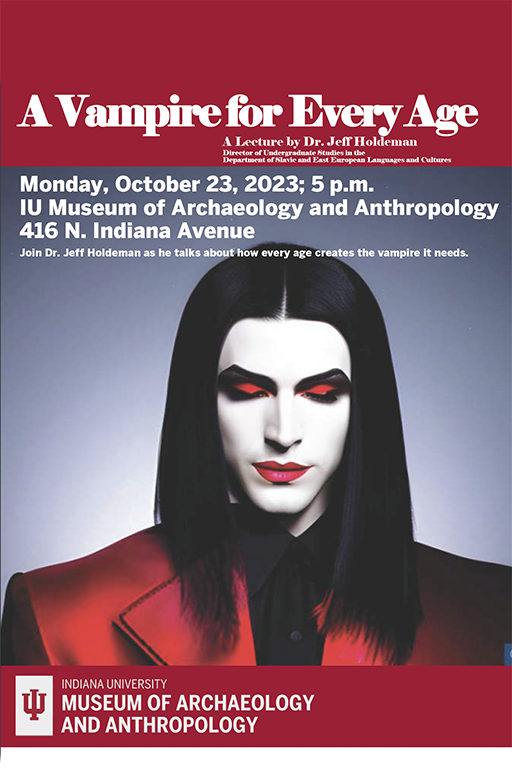

In a recent event titled A Vampire for Every Age, hosted by the IU Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, Dr. Holdeman discussed how every age creates the vampire it needs.

“We had vampire-themed snacks and a vampire display, I got some of the IUMAA staff to wear capelets, and we had a very lively Q&A after,” he said. “And it allowed students and the public to get a glimpse of the IUMAA under construction.”

Dr. Holdeman teaches courses on the vampire in European and American culture, Central and East European immigration and ethnic identity in the United States, Slavic linguistics, and Slavic language courses in Czech and Russian.

Q: What about vampires and the cultures and history around them pique your interest?

A: Vampirology is a wonderful data analysis challenge. There are millions and millions of data points that look and sound absolutely chaotic at first glance. But with a theoretical framework, analytical tools, and a lot of time and work, patterns are revealed, categories take shape, subcategories coalesce, and outliers stand out. When you bring in diachronic analysis — a study of change over time — an evolutionary story emerges which spans at least 1,500 years in the case of the Central and East European vampire that is the source of our Western vampire and its many forms.

Just as advances in evolutionary biology are making us replace the "tree of life" model with a brambly thicket model, a theoretical approach to studying vampires shows an astounding evolution with very complicated interactions between species (and their microbiomes). And just as life forms respond to changes in environment, so do the types of vampires we see.

Q: What significance would you say vampires hold in today’s society?

A: Rigorous arts and humanities training allows us to take cultural artifacts and see how they are a product of the time, location, and conditions during which they were created. A study of pre-modern folkloric vampire beliefs, 200-plus years of vampire literature, linguistic metaphor phenomena, modern sociological phenomena, etc. can tell us volumes about ourselves as humans and how we deal with "eternal" human existential crises (and their consequences):

Some folk beliefs hold that vampires don't cast a reflection in mirrors, but through this type of analysis, they all do.

Q: What was most exciting about your event at the IU Museum of Archaeology and Anthropology, and what do you hope people took away from it?

A: The most exciting part is always the joy of teaching and learning. Audiences come in expecting a list of vampire facts that maybe they think they are expected to say whether they believe or not, but they leave with the beginning of an understanding that, if we can approach vampires methodically, they will "tell" us about our human existence now and over time.

Q: You’ve been doing fieldwork in Poland and Lithuania to study Russian Old Believers since 1999. Could you explain what this work means to you, and what are some experiences that stick out to you?

A: My 2002 doctoral dissertation focused on the history of the priestless Russian Old Believers in the eastern United States: their language situation, their history since arriving in the U.S. starting in the 1880s, and how they negotiate their many identities. When I came to IU, I made it clear that I would be spending my summers in Europe in the homeland of "my" Old Believers, doing ethnographic fieldwork. I have been working to construct their migration, their settlement patterns, and the genealogies of hundreds of thousands of Old Believers and their descendants.

In my fieldwork, I pick a small town with a guest house and a bus station, hike for hours to villages, cemeteries, and prayerhouses all day long, walking the same paths that their ancestors did, talking to people about today and yesterday, reconnecting families that have been separated for over 130 years, and telling each side of the ocean about the history and fate and current lives of the other. I love showing the descendants of the Old Believers in the eastern U.S. the villages where their ancestors lived and the prayerhouses where they were baptized, the birth/marriage/death records from archives, adding generations onto their family trees, and answering questions they thought could no longer be answered. The excitement of walking into an Old Believer cemetery in a village in rural Poland and seeing that 80% of the surnames are the same as in a similar cemetery in the U.S. is an indescribable thrill. Showing them pictures at a public talk or around a laptop on the dining room table is even better.

Q: What led you to Indiana, and do you have any favorite fall traditions here?

A: The first thing that led me to Indiana was a car ride while I was an undergrad at the University of Tennessee Knoxville in the late 1980s. While other UT students were heading south to Florida for spring break, several high school friends and I piled into a car and went north on a road trip to visit our friends from high school at their universities in the Midwest. It was snowing when we arrived at IU, and we bunked in Eigenmann. We took a late-night walk into the heart of campus along the "river" next to the president's house and behind the Lilly Library, our path illuminated by lamplight and the snow. It looked and felt magical, like we had just stepped into Narnia. I fell in love with IU and its campus at that moment.

For 20 years after that, my life had connections to IU, but I hadn't been back. When a job opened up in the outstanding, nationally famous IU Slavic department, I seized the opportunity to call IU home. It has been a spectacular 20+ years so far.

As for fall traditions, when I was the faculty director of the IU Global Village Living-Learning Center from 2007 to 2017, every October I organized "language hikes" at McCormick's Creek State Park. On a Saturday in late October, at peak fall colors, we would hire a big yellow school bus (a dream come true for our international students), drive to McCormick's Creek, split up into our language clusters (Spanish, French, German, Italian, Chinese, Japanese, and I would take the Russian group), and go on nature hikes to learn nature vocabulary in our languages, practice speaking in the smells of autumn, stop for a big snack, play in the waterfall, go on a hayride, then go back to the GV and make funnel cakes and my "s'mores indoors," drink hot cocoa and local apple cider, and just enjoy each other's company and take a break from midterms and stress. It has been seven years since the last one, but every October my internal clock tells me I need to get out for a fall nature hike in our stunning south-central Indiana home.