This research direction emerged from a marked absence. "There was nothing in fashion collections for me to look at," Akou said. "I did find some objects, but only in anthropological archives and natural history museums."

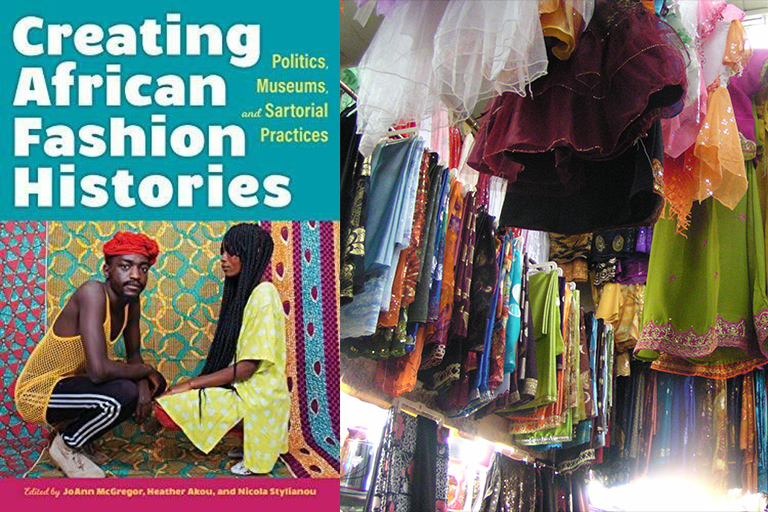

Her 2022 IU Press publication (co-edited with JoAnn McGregor and Nicola Stylianou) "Creating African Fashion Histories: Politics, Museums, and Sartorial Practices" investigates the role museums play in the study of African fashion. The anthology asks where these objects can and cannot be found, interrogating the way collections have been shaped.

Panel discussion: African fashion, museum collections

Akou will take part in a free public discussion at 6 p.m. Wednesday, September 7 at the Mies van der Rohe Building on 321 North Eagleson Ave. Fellow panelists are:

- Nicola Stylianou, post-doctoral research fellow, University of Sussex

- Allison Martino, curator of African art at the Eskenazi Museum of Art

- Beth Buggenhagen, director of the IU African Studies program

In addition to her appointment in the Eskenazi School, Akou is an adjunct associate professor in Art History, Anthropology, and Middle Eastern Languages and Cultures, an affiliate of the African Studies Program, Islamic Studies Program, and the Center for Studies of the Middle East, and a core faculty member in the Master of Arts in Curatorship program. She co-founded and co-directs the Dress and Body Association and serves on the editorial advisory board for Bloomsbury Fashion Central. As director of IU's Sage Collection in 2019, she sifted through the historic costume collection's trove of "senior cords" for an episode of the WTIU program "Journey Indiana." Akou earned a Bachelor of Arts in studio art from Macalester College and both a Master of Arts and Ph.D. in Design, Housing & Apparel from the University of Minnesota.

"Bless the hoarders and collectors of the world, because otherwise, what would I have to look at?" Akou said. "We need to collect new kinds of things, because contemporary global fashion is not being represented."

Q: African-designed clothing has not necessarily been seen through the lens of fashion history. How do museums perpetuate this approach?

A: I started doing original research on African dress—specifically, Somali dress—in the early 2000s, when I was a graduate student at the University of Minnesota. One thing I noticed immediately is that fashion collections didn’t have anything from Africa. The kinds of objects I wanted to see could only be found in art museums and natural history (ethnographic) museums. Because they were collected as "art" or "culture" and not as historical examples of dress, there wasn’t much to see. During my dissertation research at the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History, one of the curators wrote to me that she could only find a few examples of textiles from Somalia, but I was welcome to visit. Thank goodness I did, because when she opened the cabinets of artifacts, I saw many items related to dress and the body such as shoes, combs, jewelry, bags, and headrests used by nomadic men to protect their elaborate hairstyles while sleeping.

While no museum can collect everything, splitting Western dress into "fashion" and non-Western dress into "art/culture" has some unfortunate side effects: less-artistic, everyday examples are not collected, and changes in fashion are not taken into careful consideration. I can study what fashionable people are wearing in Africa right now, but what happened 50 years ago? Often, we have little idea because the artifacts are not there in museums.

Q: What would it look like to present clothing and jewelry as fashion in a museum as opposed to culture?

B: Collecting clothing and jewelry as "culture" is like taking a snapshot in time. It doesn’t give you a sense of history; it can be easy to forget that all human beings—and cultures—change over time. Collecting clothing and jewelry as "fashion," on the other hand, means that you’re always looking for things that are new ... new technologies, new designers, new consumers, new changes in society. The individual designers (and makers and wearers) are important. They are not just anonymous representatives of a culture. We know this instinctively about Western fashion, but it’s equally true for African fashion.

Presenting fashion in a museum takes some unique knowledge and skills. Hanging a flat textile on a wall like a painting might be a good way to see the structure and surface design, but in Africa, flat textiles are transformed into items of dress by wrapping and draping them on the body. That is not clear when you see a piece of cloth hanging on a wall.

Q: Your chapter in the book focuses on three IU collections of African apparel and items of adornment that you describe as "not the kinds of things that usually end up in a museum." Tell us where they came from and why they are meaningful.

A: The three collections I wrote about are all held in part or in whole at IU.

- The first, from the 1920s, was collected by an amateur ethnographer in central Congo. It’s an important collection, but it’s just one of those snapshots in time. IU initially accepted the collection as an example of “medical anthropology” from Africa. It includes amulets and divination tools, but also picks to remove insects that burrow into the feet. That’s a good example of a dress-related artifact that an art museum would probably not choose to collect.

- The second, from the 1970s, was assembled by a U.S. ambassador to Somalia, John Loughran, and his wife, Kathryn, a portrait painter. They happened to be in Somalia during a severe drought and were able to buy items of jewelry that were meaningful to Somalis, who sold them to survive—which is the purpose of expensive jewelry in nomadic culture.

- The third and most recent collection was the wardrobe of a Nigerian-Ghanaian woman, Mary Warren, whose husband was an IU graduate student in anthropology. She collected it to wear as clothing (not as "art" or "culture"), giving us incredible insight into fashion and personal choice. It also represents a way of collecting that is very consistent with Mary’s home culture. Throughout West Africa, many women collect textiles to remember histories and family members, to display their family’s wealth and good fortune, and to honor themselves and their culture.

Q: You were a studio art major as an undergrad. What led you to African fashion?

A: I was an undergraduate student at Macalester College from 1994 to 1998. The government of Somalia had collapsed in 1991 and Somali refugees were just starting to resettle in Minnesota. I often rode the public buses and I remember seeing them, but I didn’t understand exactly who they were or why they were dressing in such a distinctive way. I spent a semester in Mali during college and I was blown away by what I saw people wearing. I wanted to go back! By the time I started graduate school at the University of Minnesota, I had figured out who the Somalis were, and I was intrigued ... it was a local example of African dress. I ended up studying the history and politics of Somali dress, which became the subject of my first book, published by IU Press in 2011.

I enjoyed making textiles as a student in studio art, but it turned out that I was even more interested in learning about the makers and wearers of textiles. I had no idea that I could turn this into a career as a professor.

Q: With the rise of online platforms, African artists and designers can and do market their goods globally. While these pieces are being consumed, are we seeing them being collected like other contemporary art?

A: My new book, "Creating African Fashion Histories," came out of an exhibit and conference at the Brighton Museum. There had been exhibits of African textiles in the UK, but never an exhibit of African fashion. "Fashion Cities Africa" was the first one. The idea is clearly catching on. The Victoria & Albert Museum, which has one of the world’s best collections of fashion, is showing its first exhibit on African fashion right now.

Personally, I would argue that dress is one of the most important mediums for visual art in Africa and the African diaspora. We should honor the incredible ingenuity and resourcefulness of African artists and designers. Western museums are just starting to recognize what they have been missing out on, but there is much more work to be done ... especially in regard to permanent collections. African fashion is not being collected to the same degree as Western fashion. Not even close.

Story by Yaël Ksander.